Interiority: Six Different Ways to Show Your Character’s Thoughts on the Page [With Examples]

![Title image: Interiority: Six Different Ways to Show Your Character's Thoughts on the Page [With Examples]](https://www.aliventures.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/interiority-character-thoughts.png)

One brilliant thing about the novel (and short story) as a form of storytelling is that it gives a unique access inside characters’ minds.

If you’re writing a script for a play or for film, the only way you can directly show what a character is thinking is to have a voiceover, which can feel a little clunky. But in a novel, we can dive inside the head of one or more characters.

This is sometimes called “interiority”. It’s not just about the character’s thoughts, though that’s a big part of it. Interiority can also mean showing what they’re feeling, what motivates them, and even what biases they might have.

What is Interiority? (Definition of Interiority in Fiction)

Interiority encompasses a character’s thoughts, feelings, internal reactions, and anything else going on inside their head. Some of these might be indicated on the outside – through their expression, body language, or tone of voice – but we can only know them for sure by being in the character’s head.

There are different ways to handle showing these things on the page, so part of interiority in fiction is how the writer chooses to handle the “inside the character’s head” moments. We’ll look at some practical ways to do this, with examples, in a moment.

Why Does Interiority Matter in a Novel or Short Story?

For many readers, interiority is a huge part of the appeal of reading fiction. They feel immersed in the character’s perspective – and they love that access to thoughts and emotions, not just to dialogue and what’s happening in the plot.

Interiority, used well, can:

- Add much more emotional weight to your story.

- Increase tension, as we wonder how a character’s inner struggles will affect what they do.

- Demonstrate character growth, as part of the character arc.

- Slow down the pace, where a scene is otherwise moving too fast.

- Make your characters more sympathetic – even if they’re flawed or unlikeable.

So how do you go about giving readers access to the inside of your character’s head?

How to Show What Your Viewpoint Character is Thinking and Feeling

There are all kinds of ways you can show your character’s thoughts in the narrative – depending on how close or distant you want to keep the narrative to the inside of their head.

Here are some options to consider.

#1: Direct Thought, With Tags

Ten minutes went by. Tom paced up and down. This is ridiculous, he thought. Outrageous.

In this example, Tom’s thoughts are treated similarly to dialogue. They appear in italics (instead of in quotation marks) and the tag “he thought” is used.

This is a straightforward convention, but it’s also falling out of favour. Tags can feel clunky and unnecessary to readers, when italics alone would show that these words are what Tom is thinking.

#2: Direct Thought, Without Tags

Ten minutes went by. Tom paced up and down. This is ridiculous. Outrageous.

Here, Tom’s thoughts are shown without any kind of tag: the change to italics is enough to signal to the reader that the words aren’t part of the narrative itself, but instead a direct representation of what Tom is thinking.

Using italics for thoughts is very common across multiple genres – but it’s also falling out of favour. Some agents and editors dislike it (there’s an interesting Reddit thread here about this).

#3: Free Indirect Style

Ten minutes went by. Tom paced up and down. This was ridiculous. Outrageous.

Free indirect style (also sometimes called free indirect speech, free indirect discourse, or free indirect thought) is when the character’s thoughts are merged into the narrative itself. They use the same tense (“this was ridiculous” not “this is ridiculous”) and they’re clearly a subjective opinion … but they’re not separated out from the narrative.

This is the most popular way to indicate a character’s thoughts and feelings in contemporary fiction. You do have to be careful that it’s not confusing – but done well, it’s a smooth, immersive way to blend your character’s interiority with the action and dialogue of the story.

#4: Stream of Consciousness

Ten minutes already. Tom paced. Ridiculous, it really was. Outrageous, even. How much longer would he have to wait?

The stream of consciousness style was popularised by the Modernist writers (particularly Virginia Woolf and James Joyce). It can be a great way to establish voice, especially if you’re writing in a more literary genre … but it can also become irritating to read if you overdo it.

#5: Thoughts Flavouring the Narrative

Ten painfully slow minutes went by. Tom paced up and down.

This is one of my favourite ways to show interiority: the whole story is subtly flavoured by the character’s thoughts, feelings, judgements, and so on. It’s Tom who finds the minutes “painfully slow” here.

One drawback with this is that it can be ambiguous whether a thought/feeling belongs to the author or the character: this may be problematic if you have a viewpoint character with a perspective you wouldn’t personally uphold (e.g. they’re racist or sexist).

#6: Summarized Thoughts

Ten minutes went by. Tom paced up and down, thinking how ridiculous and outrageous it was to be kept waiting so long.

Just as you can summarise dialogue, you can summarise a character’s thoughts or feelings. This is simple and straightforward, but it has a slightly distancing effect: we’re being told what Tom is thinking, rather than being invited inside his head to view those thoughts.

This can come across as a less skillful approach than some of the other techniques, so it’s worth keeping that in mind if you’re seeking an agent/editor for your work.

What About First Person Narratives?

In a first person narrative, you have all the above choices too. You might think that in the first person, the whole story is the character’s thoughts … but some first person narrators are more detached than others, and may not necessarily be sharing everything they’re thinking. (For instance, they might be telling the story as if narrating it to a friend/therapist/audience.)

For a look at different options for the first person, read Is First Person Point of View Right for Your Story? – it goes through five different approaches, with examples of each.

Finding the Right Balance of Interiority vs Exteriority in Your Novel (or Short Story)

Balancing what’s going on inside your character’s head versus what’s going on around them can be tricky. And finding the right balance depends on your genre.

If you’re writing literary fiction (rather than commercial fiction), then you’ll likely have a stronger focus on interiority. The nuances of what your characters are thinking may be more important to your story as a whole than the plot.

In most commercial fiction, however, the balance will usually skew the other way. Your character’s thoughts, feelings, and motivations matter … but they won’t take over from the action, dialogue, and ongoing story.

Some genres do use more interiority than others – it really helps here to read widely in your chosen genre and sub-genre. For instance, romance fiction will usually spend a reasonable amount of time on people’s thoughts and feelings. Action-driven adventure stories won’t have a lot of interiority … but psychological thrillers will.

As you work on your story, watch out for long passages of interiority. If your character is just thinking at length – but not doing anything, or making any decisions – then you probably need to trim things down.

Giving the reader an insight into what your character is thinking and feeling can make your novel richer and more engaging. You might add tension, increase the reader’s empathy for your character, or simply use interiority to slow down a too-fast scene.

For more on viewpoint and conveying your character’s thoughts, take a look at:

- Mastering Third Person Limited Point of View: Four Options and Four Examples

- Is First Person Point of View Right for Your Story? Five Approaches (+ Examples)

- Do You Head-Hop? Getting Third Person Point of View Right

- Choosing the Right Viewpoint and Tense for Your Fiction

- What is an Omniscient Narrator and Should You Use One?

- Split Narratives: Dividing Your Story Between Two or More Narrators

About

I’m Ali Luke, and I live in Leeds in the UK with my husband and two children.

Aliventures is where I help you master the art, craft and business of writing.

Start Here

If you're new, welcome! These posts are good ones to start with:

Can You Call Yourself a “Writer” if You’re Not Currently Writing?

The Three Stages of Editing (and Nine Handy Do-it-Yourself Tips)

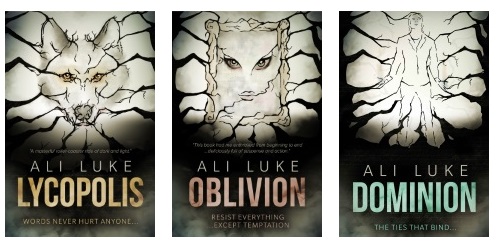

My Novels

My contemporary fantasy trilogy is available from Amazon. The books follow on from one another, so read Lycopolis first.

You can buy them all from Amazon, or read them FREE in Kindle Unlimited.

0 Comments