What is an Epistolary Novel? Pros, Cons, and Examples of Epistolary Fiction

You might have heard the term “epistolary novel” bandied around in writing circles or book groups. An “epistle” is a letter—and “epistolary fiction” just means a story written in the form of letters.

These days, stories that are written as diary entries, text messages, emails, and more all count as epistolary too. Essentially, if we’re supposed to imagine that the character has written the text we’re reading, then it’s an epistolary novel.

We’ll dig a bit more into that, before looking at some types of epistolary novels, the pros and cons of the epistolary form, and some specific examples of contemporary epistolary novels across a range of genres.

What is an Epistolary Novel?

An epistolary novel is a novel that’s told through letters, emails, diary entries, newspaper reports, or other fictitious texts. Sometimes, all the text is written by the same character (in the form of diary entries or only one side of the correspondence); other times, we have back-and-forth letters, or multiple different formats.

The epistolary novel goes back a long way—to the late 17th century, in England (and earlier elsewhere in Europe). Many classic 18th century novels are epistolary, like Samuel Richardson’s novels Pamela, Clarissa, and The History of Sir Charles Grandison and Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses … but the epistolary form isn’t consigned to history. The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society (2008) is entirely composed of letters, for instance.

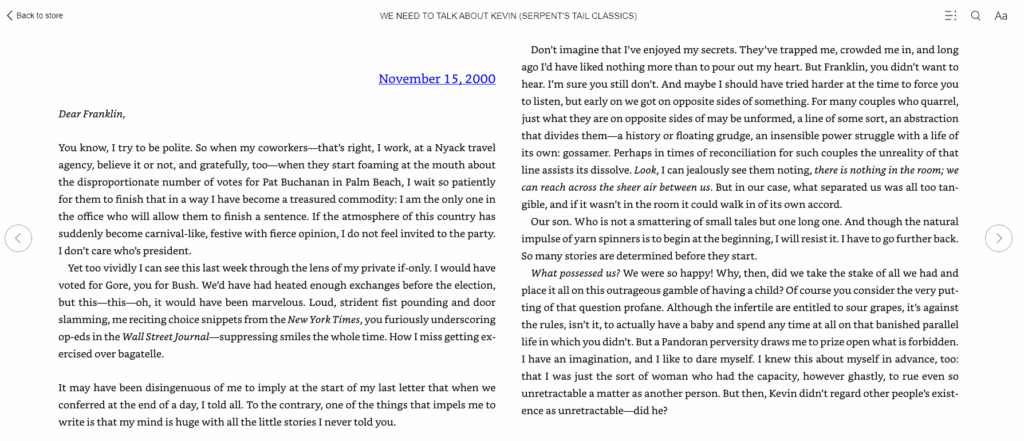

Here’s how a letter might look in an epistolary novel (this is from We Need to Talk About Kevin by Lionel Shriver).

We’ll come onto some examples in detail towards the end of this post—but if you want a few examples of epistolary novels you might have read in addition to the ones I’ve already mentioned, here are a few across different time periods and genres:

- Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley (told in the form of letters written by the narrator Robert Walton, who is recording the story told to him by Doctor Frankenstein)

- Dracula, by Bram Stoker (told primarily through Jonathan Harker’s journal, but also through other characters’ journals, diaries, letters, telegrams, and newspaper articles)

- The Screwtape Letters, by C.S. Lewis (told through letters written by Screwtape to his nephew Wormwood)

- The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 ¾, by Sue Townsend (as you might imagine from the title, this is told as a diary)

- The Doors of Sleep, by Tim Pratt (told through journal entries written by the main character, Zaxony Delatree)

- The Perks of Being a Wallflower, by Stephen Chbosky (coming of age story told as a series of letters from the protagonist Charlie to someone anonymous)

Different Types of Epistolary Novels

Any two epistolary novels can look very different from one another—this is a highly flexible format! But some common ways we might break down different epistolary novels are as follows:

Epistolary Novels From a Single Character Perspective

Some epistolary novels are from one character’s perspective: usually, they’re a diary written by that character alone, or they’re a one-sided series of letters (we might be led to imagine the responses, but they aren’t actually included).

Having the perspective of just one character makes a lot of sense when the novel is in the form of a diary … but it can also work for a letters-based novel. The Screwtape Letters, for instance, consists entirely of Screwtape’s letters. We don’t see any of Wormwood’s replies, though Screwtape often refers to these.

Epistolary Novels Giving Multiple Characters’ Perspectives

One fun thing about the epistolary form is that it makes it easy to bring in lots of different voices and perspectives (even if one character or perhaps a pair or small group of characters is the focus).

Clarissa, for instance, has letters from four main characters (Clarissa herself, the protagonist; Lovelace, the antagonist; Anna Howe, Clarissa’s best friend; and John Belford, Lovelace’s friend)—but there are more than 20 different characters in total who write letters.

Epistolary Novels Using Mixed Formats (Letters, Emails, Texts, Diaries…)

Some epistolary novels stick with just one format (commonly, diary entries or letters). But many will blend together a whole series of documents, like Bram Stoker’s Dracula does. Stoker launches straight into the narrative with Jonathan Harker’s journal, which tells the story of how he goes to stay with Count Dracula. When this breaks off at the end of Chapter 4 (with Jonathan fleeing the castle), the narrative is taken up by Mina’s letter to Lucy. After that, we have multiple letters, diary entries, telegrams, a newspaper clipping, a ship’s log, even business letters.

Epistolary Novels That Only Reveal Their Nature at the End

One twist on the epistolary novel is to write as if producing a regular first person narrative—only to reveal its epistolary nature in an epilogue. Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale does this, as does Ian McEwan’s Atonement. This can make for an interesting twist that changes how we see the whole novel.

Advantages of the Epistolary Form

So why do writers use the epistolary form at all—and is it worth considering for your own novel (or even for a short story)?

Some great advantages, compared with simply writing in the first person, are that epistolary fiction offers:

#1: An insight into how characters portray themselves in writing. The way characters write can help us get a sense of who they are (just like the way they speak conveys this). Are they ponderous and long-winded in their letter writing? Slapdash? Funny? Some characters might come across very differently in writing from in person—they might even be keeping a secret diary or writing under a pseudonym.

#2: The use of the first person perspective without us being confident the protagonist won’t die. In most first person narratives, the reader assumes the protagonist will survive to the end (because who would be telling the story, otherwise)? While writers can get round this by having a first-person narrator die and someone else finish the story, the use of letters and diaries can add more of a sense of uncertainty: someone else could have found the character’s writings after the character died.

#3: The ability to use multiple first-person points of view. You might be able to juggle two or three first-person narrators in a conventional narrative, without confusing your reader—but you probably can’t go much further. By using letters, diary entries, emails, texts, etc, you can give the first-person perspective of even quite minor characters … while keeping everything clear for the reader.

#4: Additional creative scope—or even a sense of playfulness. When you’re writing a conventional first person narrative, even with two or more narrators, the “voice” of your character(s) is going to remain pretty consistent. But with an epistolary novel, you can include all kinds of voices and texts, from very informal texts to business letters. You can get creative and have fun with this, e.g. with texts being written in real time and perhaps interrupted.

#5: A good excuse for an unreliable narrator. In straightforward stories, a first-person narrator can be unreliable (either deliberately misleading the reader or simply through being naive) … but it may be easier to pull this off well if you use the epistolary form. The character might manipulate or outright lie through their letters, or wildly exaggerate in their diary.

#6: The use of letters, diary entries, or other epistolary forms as part of the plot. Depending on the type of story you’re telling, the letters (etc) that you use could easily become significant in the actual storyline. Perhaps a letter goes astray, an important email gets lost in the ether, a text message is accidentally sent to the wrong person … or maybe someone even tampers with the text itself, or fakes a message from one character to another.

#7: More freedom with spelling, punctuation, grammar, and formatting. If you’re presenting what’s supposed to be your character’s words, then you’ve got plenty of scope to use things like text message abbreviations, spelling mistakes that show your character is very young or poorly educated, or even unconventional punctuation (like ??? or !!!) to indicate emotion.

Disadvantages of the Epistolary Form

Why might you not want to use the epistolary format for a novel or short story, then? There are some distinct drawbacks, particularly if you’re writing commercial genre fiction.

- Some readers simply don’t like the epistolary format. Just like some readers dislike first person narratives, some won’t like epistolary novels. They may find these novels confusing or hard work to read, or simply find it hard to immerse themselves in the story world because their attention is too drawn to the artifice of the novel.

- Mainstream genre fiction doesn’t tend to use the epistolary form. In pretty much any genre, you’ll be able to incorporate epistolary elements … but you might find it a harder sell to tell the whole thing as a diary or series of letters.

- It could be tricky to develop a complex plot within an epistolary form. If you’ve got lots of different characters writing letters all the time, or if there’s a complex interconnected series of events, you may find that readers struggle to keep up with what’s going on.

- The epistolary nature of your novel needs to fit with its subject matter. The reader needs to believe that your characters would be writing this amount of material as letters, diary entries, emails, etc. If you’re writing a fast-paced thriller, your characters are highly unlikely to be writing long, coherent letters in the middle of car chases and shootouts.

Four Examples of Epistolary Novels

Let’s take a look at some examples of epistolary novels from a range of genres.

The Doors of Sleep, Tim Pratt (science fiction)

I fell, and everything went gray, but I bit my own tongue and willed myself to stay awake. If I passed out now, I might well bleed out wherever I woke, unless I happened to open my eyes in a trauma center, which wasn’t likely. Here, at least, Minna might be able to do some first aid, make a tourniquet or something – farm people knew about that stuff, didn’t they?

That all sounds so logical and deliberate, as I write it down after the fact. Actually I was screaming and bleeding and terrified. Minna said something my virus translated as “Gosh!” and then the pain at my elbow went away, replaced by spreading coolness. I turned my head, heavy as a cannonball, and saw Minna rubbing a cut piece of yellow fruit on my wound. My gaze drifted downward and I watched the bleeding end of my arm close over, new flesh growing across the wound in seconds. I was maimed, but I wouldn’t bleed to death.

The Doors of Sleep is written as a journal (in fact, it’s one book of a two-part series, titled The Journals of Zaxony Delatree). It begins in the middle of Zaxony’s adventures, so he spends quite a bit of time filling us in on the backstory as the book progresses.

In this short excerpt, we see one of the interesting features of this kind of first person narrative: it’s told somewhat “after the fact”. As Zaxony writes, he’s relatively calm and logical—a little at a remove from the events that have taken place.

Bridget Jones’ Diary, Helen Fielding (romantic comedy)

Tuesday 3 January

9st 4 (terrifying slide into obesity — why? why?), alcohol units 6 (excellent), cigarettes 23 (v.g.), calories 2472.

9 a.m. Ugh. Cannot face thought of go to work. Only thing which makes it tolerable is thought of seeing Daniel again, but even that is inadvisable since am fat, have spot on chin, and desire only to sit on cushion eating chocolate and watching Xmas specials. It seems wrong and unfair that Christmas, with its stressful and unmanageable financial and emotional challenges, should first be forced upon one wholly against one’s will, then rudely snatched away just when one is starting to get into it. Was really beginning to enjoy the feeling that normal service was suspended and it was OK to lie in bed as long as you want, put anything you fancy into your mouth, and drink alcohol whenever it should chance to pass your way, even in the mornings. Now suddenly we are all supposed to snap into self-discipline like lean teenage greyhounds.

A hugely bestselling epistolary novel, Bridget Jones’ Diary came out in 1996 and is often seen as the book that kicked off the “chick lit” movement. Through Bridget’s diary, started on New Year’s Day, we see her attempts to lose weight, quit smoking, and find a boyfriend, while struggling with all the usual trials and tribulations of life. The plot is inspired by Pride and Prejudice (which, interestingly, is thought to have started out as an epistolary novel in Jane Austen’s early drafts).

In this excerpt, we see how epistolary writing lends itself to a clipped, informal style (e.g. with the abbreviation “v.g.” for “very good”,and the use of phrases like “have spot on chin” instead of “have a spot on my chin”).

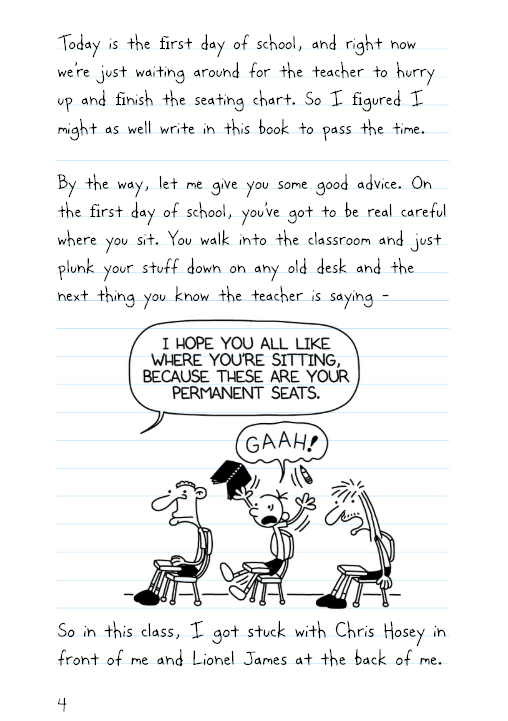

Diary of a Wimpy Kid, Jeff Kinney (children’s novel)

You might not think of the epistolary form for a children’s novel, but The Diary of a Wimpy Kid series has been going strong since 2007, and is highly popular for its cartoons and funny plotlines. (Another great example of a very popular epistolary children’s novel is The Story of Tracy Beaker.)

Diary of a Wimpy Kid uses a handwriting-style font, along with frequent cartoonish drawings and a lined background, to make the book look like a “real” diary. It also makes it an easy, appealing read for children.

The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows (historical fiction)

Mr Sidney Stark, Publisher

Stephens & Stark Ltd

21 St James’ Place

London SW18th January 1946,

Dear Sidney,

Susan Scott is a wonder. We sold over forty copies of the book, which was very pleasant, but much more thrilling from my standpoint was the food. Susan managed to get hold of ration coupons for icing sugar and real eggs for the meringue. If all her literary luncheons are going to achieve these heights, I won’t mind touring the country. Do you suppose that a lavish bonus could spur her on to butter? Let’s try it – you may deduct the money from my royalties.

Now for my grim news. You asked me how work on my new book is progressing. Sidney, it isn’t. English Foibles seemed so promising at first. After all, one should be able to write reams about the Society to Protest Against the Glorification of the English Bunny. I unearthed a photograph of the Vermin Exterminators’ Trade Union, marching down an Oxford street with placards screaming ‘Down with Beatrix Potter!’ But what is there to write about after a caption? Nothing, that’s what.

The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society tells the story of Nazi-occupied Guernsey during the second World War. It consists of letters, primarily between Juliet (a writer, looking for her next book idea) and Dawsey (a member of the titular society, who contacts Juliet). As Juliet continues her correspondence with Dawsey and other members of the society, she becomes even more intrigued by their story and visits Guernsey, slowly falling in love with Dawsey.

The epistolary format may not be nearly so common today as it was in the 18th century, but it’s still well worth considering. Even if you don’t write a fully epistolary novel, you might want to incorporate epistolary features into a more straightforward narrative, such as a letter, diary entry, or newspaper report. Or, you might experiment with this format in a short story.

Want more writing tips? Join the Aliventures newsletter list. You’ll get an exclusive short article about writing each Monday, plus an in-depth blog post every Thursday. Just pop your email address in the box below:

About

I’m Ali Luke, and I live in Leeds in the UK with my husband and two children.

Aliventures is where I help you master the art, craft and business of writing.

Start Here

If you're new, welcome! These posts are good ones to start with:

Can You Call Yourself a “Writer” if You’re Not Currently Writing?

The Three Stages of Editing (and Nine Handy Do-it-Yourself Tips)

My Novels

My contemporary fantasy trilogy is available from Amazon. The books follow on from one another, so read Lycopolis first.

You can buy them all from Amazon, or read them FREE in Kindle Unlimited.

0 Comments