How to Add Tension and Pace to a Scene That’s Sagging

Some novel scenes speed along, taut and tense, and full of energy.

But others drift, with your characters ambling around, chatting or thinking, not really doing anything much at all. The pace sags … and the tension might feel non-existent.

For a lot of novelists, this tends to happen somewhere in the middle of the novel. You might have a bunch of scenes that don’t really have a huge amount happening: they’re not necessarily progressing the story at all.

So what can you do to improve a sagging scene? And how can you spot one in the first place?

Five Warning Signs of a Sagging Scene

You might have a sagging scene if:

- Beta readers have told you that a scene isn’t really working.

- You have a sense that nothing really happens in the scene. Maybe it felt boring to write (or rewrite).

- The bulk of the scene involves characters chatting or hanging out, with little or no conflict between them.

- You could cut the scene completely … and it wouldn’t affect your plot at all.

- The scene mostly exists to give the reader some backstory on your characters or to explain something in the story world.

Sometimes, a scene like this just has to go. Perhaps you wrote it to hit your daily word count goal … you just kept the story rolling along, even though you didn’t have much happening. And you realise, as you rewrite your novel, that the scene just doesn’t belong at all.

If this happens … don’t feel bad about it! I firmly believe that no word you write is ever wasted. The scene might have hugely helped you develop your thinking and your characters, even if it doesn’t appear in your finished novel.

Assuming you do want to keep the scene, though – perhaps it contains some really important moments or even forms one of your key plot points – then here’s what you can do.

Ten Ways to Add Tension and Pace to a Sagging Scene

#1: Get in Late, Get Out Early

My wonderful editor Lorna Fergusson taught me this rule for scenes: get in late, get out early.

That means, don’t have a “warm up” paragraph or two where you’re setting up the scene. We don’t need to see your character getting into the car, buckling their seatbelts, deciding on the music, and so on … we can jump straight to the moment where an argument is starting. The reader will pick up the context, and your scene will pick up the pace:

“We haven’t moved in half an hour.” John was scowling out of the windscreen at the line of cars ahead, as though that was going to get the traffic to miraculously start moving. “I knew we should have taken the other route.”

Similarly, end the scene on a strong note. That might be a powerful line of dialogue, a decisive action, or an ominous thought occurring to your character. Don’t have a “winding down” at the end of the scene where the pace slows to a crawl.

#2: Raise the Stakes of the Scene

Scenes can lack tension if there’s not much at stake. While obviously not every scene is going to involve a life-or-death situation, you can often ramp up what’s at risk.

That might mean things like:

- Adding time pressure: a journey to dinner with a new girlfriend’s parents might feel a bit fraught, but it’s going to be a lot more tense if there’s a missed train connection involved and the clock is ticking…

- Having a consequence to failure: a difficult meeting with a client might be frustrating, but it could feel a lot more important if the protagonist’s anticipated promotion or payrise relies on this meeting going well.

- Making a choice that can’t be undone: maybe instead of a character “borrowing” a friend’s prized fountain pen to use it for a while, they take it and accidentally damage it, so they’re unable to give it back.

- Putting other characters at risk: a journey to find food in a harsh environment might feel all the more perilous if there are others relying on that food being brought back.

- Adding an audience: asking out someone you fancy can be nerve-wracking … but it’s a whole lot worse if there are other characters watching on, waiting to see whether it’s a “yes” or not.

#3: Cut Chit-Chat Dialogue (or Add More Subtext)

I’ll admit I fall into this one when I’m drafting: it’s very easy to have characters chat to one another about nothing particularly important.

In real life, most of us do this kind of small talk all the time. But if your characters are talking about nothing much at all, it can feel a bit pointless – and certainly not tense – to the reader.

You can either:

- Cut out any chit-chat altogether. Jump into the main bit of the conversation: we can assume the pleasantries!

- Add more subtext to the conversation. Perhaps your character’s conversation with her mother about the weather is laden with years of pent-up resentment on both sides.

#4: Watch Out for Info-Dumps

In some novels, you might need to get a lot of information across to the reader. Perhaps they need to know the historical context for why characters are behaving in a particular way, or you need to explain how your space station works, or what the long and troubled history is between two groups of people.

But info-dumps can feel boring and heavy-handed to readers. We don’t want to read something that seems like a summary – or a textbook.

If you’ve got a sagging scene that you can’t cut because it’s packed with essential information, look for a more dramatic way to convey this. It might be through something like:

- An argument between characters.

- A character discovering a secret.

- A newcomer misunderstanding the rules.

- Conflicting accounts from each side.

- Inference: simply show the reader something and let them pick up the meaning.

#5: Introduce Unanswered Questions

One of your most powerful tools for keeping readers turning the pages is the unanswered question. If you can introduce a mystery or make the reader anxious about a character, that can add a bit of extra tension into a scene that’s otherwise quite low-key.

Unanswered questions can be almost anything. They might be about the past (backstory), about the future (what’s going to happen), or even about the present (in a story where the setting might be mysterious or confusing, for instance).

#6: Merge the Saggy Scene With Another Scene

If you’ve got a scene that’s not strong enough to stand alone, could you merge it with another scene? Perhaps it’s too short, if you cut out all the chit-chat … but you could bring the important bits into a different scene, strengthening both.

For instance, if you’ve got a conversation over coffee between two characters where one reveals an important detail about her past, then you might be able to use that conversation in a scene that’s already more tense – an argument, for instance, or a rushed journey against the clock.

#7: Add or Remove Characters from the Scene

Some scenes get bogged down because they have too many or too few characters in them.

If you’re juggling six characters and trying to include everyone in the conversation, it might feel slow and lack tension. Paring the scene down to the three characters who this conversation matters to might fix it instantly.

Alternatively, if two characters are having a fairly dull back-and-forth conversation, adding in a third might bring more tension – particularly if that third character plays a more antagonistic role, tries clumsily to “help”, or creates a personality clash.

#8: Bore the Character, Not the Reader

This might seem obvious, but don’t bore your reader to show that your character is bored!

In a Regency novel, your heroine might be faced with a boring, pompous suitor who drones on and on … we don’t need to hear their whole speech. Instead, we could have the heroine switching off and daydreaming about something else, or trying to concoct excuses to get away.

#9: Have Physical Action Taking Place

In your scene, something needs to change. While that change might take place purely inside your character’s own head, you also need something to happen in the scene. (If they just sit in a comfy armchair, thinking hard, it’s unlikely to be a very interesting scene.)

Editor Alice Sudlow has a great article about the “physical, literal actions” of scenes. One way to think of this is to imagine staging your scene or watching it on TV. What action would you see?

#10: Trim Down Thoughts (Don’t Have Characters Ruminate Endlessly)

Often, your viewpoint character will be feeling something strongly: perhaps guilt, sorrow, anger, self-doubt – or maybe a more positive emotion, if they’re falling head-over-heels in love.

A scene can end up feeling a bit slow-paced, though, if you keep repeating the same emotional notes or having your character go over and over the same ground in their thoughts. It can be helpful to bring in more action and dialogue: show what the character is feeling and thinking, don’t just tell us.

Here’s a quick checklist, based on all the tips above, that you can run through to edit any sagging scene:

- Get in late, get out early. Come straight in at the first interesting point. End the scene strongly, don’t wind down at the end.

- Raise the stakes. Make the consequences of failure matter to your character – and you’ll automatically add a lot more tension.

- Cut chit-chat. Stick to dialogue that actually says something (though this might well be through subtext or through what’s not being said).

- Watch out for info-dumps. If the reader really needs the information, work it in through conflict, or let the reader infer it through dialogue and action.

- Introduce unanswered questions. Get the reader wondering why a character behaves a certain way or what is hidden in that locked drawer.

- Merge two scenes together. If you’ve only got enough strong material for half a scene, try working it into a different scene of your novel – it could strengthen both.

- Add or remove characters. Perhaps a conversation would be better-paced (or more tense) if you remove people who aren’t contributing and/or add people who cause conflict.

- Bore the character, not the reader. You can absolutely have boring, tedious, long-winded characters in the novel … but convey that through your viewpoint character’s boredom.

- Have physical action. Something needs to be happening in your scene – not just thoughts, but something we could see in a filmed version of your story.

- Trim down thoughts. Don’t have a character endlessly go over and over the same ground in terms of their emotions and thinking. Use dialogue/action to show what’s going on in their head, too.

Want More Help Editing Your Scenes? (Free Quick Reference Guide)

Pop your name and email address in below to get a free copy of my “quick reference” guide from Editing Essentials. It goes through 20 common writing mistakes so you can fix them as you edit.

About

I’m Ali Luke, and I live in Leeds in the UK with my husband and two children.

Aliventures is where I help you master the art, craft and business of writing.

Start Here

If you're new, welcome! These posts are good ones to start with:

Can You Call Yourself a “Writer” if You’re Not Currently Writing?

The Three Stages of Editing (and Nine Handy Do-it-Yourself Tips)

My Novels

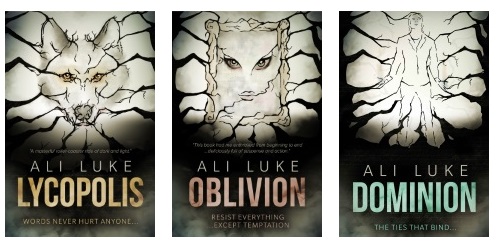

My contemporary fantasy trilogy is available from Amazon. The books follow on from one another, so read Lycopolis first.

You can buy them all from Amazon, or read them FREE in Kindle Unlimited.

0 Comments